Digital artist Rafaël Rozendaal on NFTs and how the art world is like a video game

The Ideaspace publishes essays and interviews with authors, artists, designers, economists, researchers, activists, and others exploring the frontiers of value and self-interest.

INTERVIEWEE: Rafaël Rozendaal

BACKGROUND: Artist shown at Centre Pompidou, Whitney Museum, Times Square

TOPIC: NFTs and how the art world is like a video game

LISTEN: On the web, Apple, Spotify, RSS

“For me, boredom is the main source of creativity. It's a negative state in the sense that you tend to avoid it instinctively. When you're in line at the post office you'll check your phone to see what's going on. It's very natural for us to seek information. Art time is when you shut out information.” — Rafaël Rozendaal

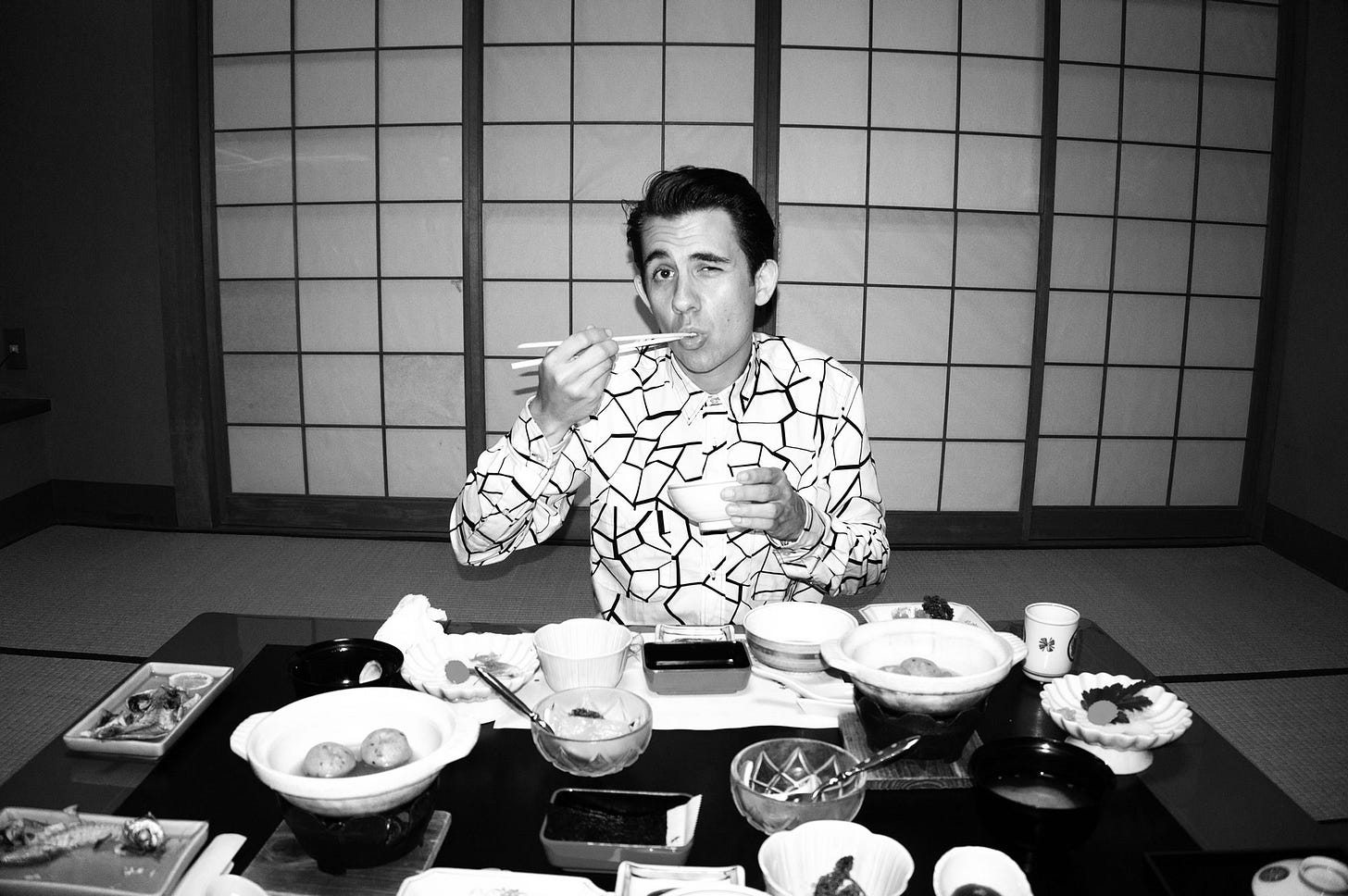

When I lived in New York I had a weekly lunch date with my good friend, the artist Rafaël Rozendaal. We’d meet at Barrio Chino in the Lower East Side, sometimes catch a movie at Metrograph after. I was in the early stages of writing This Could Be Our Future and he was producing new work in a variety of mediums, including lenticular paintings, tapestries, and websites.

The website is Rafaël’s primary medium as an artist. He makes standalone websites — some interactive, some with audio, all in motion — that are works of art. They’re beautiful, hypnotic, striking, mesmerizing. They make you smile and draw you in. Three of my favorites:

There are more than 100 of these, each one its own universe. The work has not gone unnoticed. Rafaël is frequently recognized as a pioneering digital artist, his websites get more than 40 million pageviews a year, and he’s in the Whitney Museum’s collection.

Earlier this year (and partially at my suggestion) Rafaël made new work available for sale as NFTs. Several unexpectedly sold for six figures, and Rafaël has found himself one of the early stars of the new medium.

Today Rafaël joins the Ideaspace to share his hopeful but punk rock guilt-ridden feelings about the experience, his explanation for how the art world is like a video game, and great advice for cultivating creativity. Listen to our full conversation on the web, Spotify, or Apple. Read a condensed transcript below.

YANCEY: I was reading an artist’s statement for a gallery show you have coming up later this year where you explain your work with websites. You say:

“My idea was simple. I did not want to make a website that showed IRL documentation, I wanted to make websites that take advantage of the possibilities of the browser. These works are generative moving images. They're not videos or animations. They are code-based algorithms. They behave like a fountain or a waterfall, always doing the same thing, but never repeating itself.”

Can you explain what your work is about?

RAFAËL: I always say my work is not about something, but it is. There's a difference. When you think of an icon for software on your home screen on your phone, that's not the software. That's a link, and then it opens the software. That's how a lot of people see art. They're like, “I'll look at the painting, but then it will tell me a story so I can go to bed and understand it and know everything's okay.” People want closure the same way they want to see the ending of a movie. But I see art the same way you would look at a flower or a tree or a glass of milk. You don't have to think, “What does this mean? What story will this tell?” You just look at it and say, “It's interesting how this tree moves in the wind.” And that's it. You don't have to attach any value, but you can. With my work I have a problem with the word “about.” But I don't even think that's what you’re asking.

YANCEY: No, but I love that. That was great to hear. I meant how your websites are generative, how they’re living.

RAFAËL: I can tell you how it started. You start with the computer. You can't paint on a computer the same way you can on canvas. You can try, but it's different. Then you start thinking, “What can I do here that I can't do in traditional media?” I tried animating things in After Effects, the video program. I would make an animation and it was pretty interesting, but then I couldn't put it on the internet because it was too big. Or I would have to compromise the work and really process it to a small size and it didn't look as good as it could. I started playing with Flash and later JavaScript, and you could make these line-based images that are scalable. At first it was just an animation, but then even with the animation I would run into problems, things I couldn't animate. The best example is this website “Stagnation Means Decline,” which has stacks of dollar bills rising.

I was animating it and the computer would crash all the time because it was so many objects, too much for computers at the time to handle. Then I met a coder, Reinier, who said, “If we don't have too many instances of the dollar bills, but just enough to cover the background color, then with code I can just flip the layering of them.” He solved it with code.

The benefit of solving it with code is that we didn't have to have a beginning or an ending. People see the work and they're not sure if it's random or animated. For a lot of people it doesn't matter. But you can feel it. It's the same as screen savers. The most interesting thing for me as a maker is that with a code-based work it's very easy to change things later. When a work is code-based you have all these numbers that you can change — make it go faster, make it go slower. It's a bit like when you make a soup. If you add too much salt it's very hard to get rid of the salt. But with a code-based work you can change the parameters even at the end.

YANCEY: What has it been like telling people you make websites that are artworks? Is that hard for people to understand?

RAFAËL: I think so. Especially in the beginning. When you would say that people are like, “Oh, great, I need a web designer.” People knew certain people build websites, and it was kind of mysterious in the late ‘90s. If you could make a website, you could make just any website, you could make a lot of money. Then I would say, “No, I'm not a web designer. I use it as my medium. I'm an artist.” Many artists feel this — it's very hard to explain your work but it's very easy to show it. When internet phones started appearing that made it a lot easier. You’re somewhere at a dinner or a party and someone says, “Oh, what do you do?” "I'll just show you.” Showing it makes it a lot easier.

YANCEY: This isn’t a socially nice question, but how much do these websites sell for?

RAFAËL: I sold the first one for €2000. It’s a random starting point. There were a couple of people who were experimenting with work in domain names and we were talking about, “What's the price of a photo? What's the price of etc?” It was just guesswork. Pricing of art is very weird. Why is that abstract painter worth more than the other one? Things don't make sense. It’s like a video game. The whole world is becoming like that. Pricing in the art world is based on cultural capital: which shows have you done, have you had institutional support, have you shown in museums. It's very similar to a video game where you eat this potion and then you get a bigger sword or you get a bigger weapon or something. It's exactly like that. It's like, “Go have dinner with this person, they'll let you through that door, then you can do something there.” It has nothing to do with the making, but it also does because it brings energy and confidence and production and better documentation.

YANCEY: Earlier this year we had a conversation where I called and asked if you’d checked out NFTs because I thought it seemed interesting for you to try. My main takeaway was I didn't think the art was particularly interesting, but the form was. In that conversation you were skeptical. I wonder if you can remember what was in that skepticism.

RAFAËL: Many different things. As you said, my work is code-based. NFT is a bit like Instagram where it favors either pictures or videos, so I wasn't sure about that limitation. Then the whole abstraction of money, decentralization of the internet and open source, those things feel fragile and user-hostile. I like software that's smooth and friendly and mass audience. That was a hesitation. There's been many trends in digital. A lot of them I didn't like — VR happened and a lot of artists jumped on VR, but I never liked the feeling of a helmet on my head. 3D printing I was not so interested in. There's always these consultants with buzzwords selling you something. The price you pay is your attention. I'm always careful with my attention. Am I going to add another facet to my life that will take away from concentrated sketching time?

NFT came along and my first thought was, “If there wasn't any money in this, would I be interested in it?” But you can't just think about it, you have to try it. Once you try it, you understand this idea of permanent ownership and how that's a whole different feeling. I was hesitant and then it was very successful, much to my surprise.

YANCEY: Since we had that conversation you've put up, as of this recording, five works on Foundation as NFTs. The first of those did better than you expected: it sold for $190,000 in Ethereum. Afterwards, you texted me, “I hope this doesn't end up with me having the head of a horse,” referring to the movie Sorry to Bother You. What did you feel when you had that unexpected success?

RAFAËL: I had worked for so long almost at a breakeven point with my digital work. I would get fees for showing work or selling work, but there's also a lot of costs in maintaining the server and programmers and all that. I did okay, but my income for someone living in New York was quite low. Then someone gives you a raise that’s 100-fold in one day — it feels like someone's gonna say, “Hey, I supported you. Now you owe me big time.” There's a price to pay. There's no free lunch or something. When you increase 3% every year I don't think you have that feeling. But when all of a sudden in one day your hourly rate goes up 100-fold it’s a strange feeling. Maybe I'm a bit paranoid, but I was like, there must be something weird about this. Why would someone spend this much on something that last week was priced 100 times less?

YANCEY: Why is that? Is there something weird?

RAFAËL: One of the things that's very clear to me now is there's an internet audience and there's the circle around galleries. Each gallery has its own circle of clients and those were very mismatched. I've always had a big internet audience, so that's a way I could justify that price. When the internet started, before social media, I had an audience of, the first ten years and even now, more than 40 million people per year. Some years 60 to 65 million people would visit all my websites combined. I've always had this huge audience that I couldn't directly monetize. I would do an exhibition and there was a mismatch of generations. Because the exhibition, like you said, you have to explain “Why is this art?” These were people that were not tech-savvy, not digital-first. Then there was this huge digital-first audience that couldn't come to the exhibition because it was so local. There was a mismatch of energy. Now just because now the work has a “buy” button right next to it, that changes it so much.

YANCEY: Watching this made me wonder if this is the result of a domain switch. In the past you were a digital artist working in the physical world trying to justify a different medium. Now you're a digital artist operating in a digital world. The value systems are native so there’s this click.

RAFAËL: That’s a good point. One of the things that's interesting in the gallery space is still images are at an advantage over moving images. In the physical world paintings are the most user-friendly. In the digital world moving images are an advantage. I'm good at moving images. All of a sudden you enter this world where what before was difficult now is actually a plus.

YANCEY: Looking at the five pieces you've done so far a few things stand out. One is that, just in terms of the price being paid for your work, it's been steadily increasing. Because of that I know you've released work that you thought would be less interesting to disrupt that growth trendline.

RAFAËL: That's called punk rock guilt.

YANCEY: Why punk rock guilt?

RAFAËL: It's a shock. Because I moved around so many times to different countries, I kept downsizing my belongings so I developed this whole personality and ethos around not owning anything, just being able to pack up and leave and go wherever I wanted. The most precious things to me are headspace, time, and attention. Money and things take over your brain. The other thing that's weird is the money is public. You interviewed another artist recently and you probably have no idea what their income is. That's nice. Why would you want people to know the income? You want people to look at the work. Maybe it's not punk rock guilt, but it is this weird public-facing “Oh, now everybody knows exactly how much I was paid for this work at that time."

One of the first reactions was that my gallery in New York kicked me out because they were starting their own NFT platform and they weren't happy that I was on another one. I work with three different galleries — now two — and there was a bit of tension there: “We invested time in you, and now another platform sells your work.” There's a conflict there, and maybe that's a general disruption where the older business model has to adapt. There were different outbursts of weird energy from people towards me. That would have never happened if these works were sold in a gallery and no one knew the price. It's fine. I understand the whole gamification of this platform and that the whole fun of it is that it’s public. I'm getting more used to it, but it was a shock.

YANCEY: The other day I was talking to you about some challenging feelings I was having about working by myself so much. You said to me something to the effect of, “That's what's hard about artist time.” You used this phrase “artist time.” Can you talk about artist time?

RAFAËL: I often hear this idea of “flow,” being in the flow. I find that I can be in the flow with practical matters — video compression or answering emails, that kind of stuff. But the creative act itself for me is not a state of flow. It’s more like fishing or waiting. You throw out your fishing line and you wait. One of the things I noticed as time went by and the mobile phone came along and there’s more and more entertainment is that it's harder and harder to be bored. For me, boredom is the main source of creativity. Maybe that's similar to meditation or quietness, but to me it feels like boredom. It's quite a negative state. It's negative in the sense that you tend to avoid it instinctively. Whenever you're in line at the post office or whatever, you'll check your phone to see what's going on. It's very natural for us to seek information. Art time is when you shut out information.

I just saw an interview with Steven Spielberg. He said the regular world shouts and intuition whispers. That sounds a little bit corny but I think it's very true. You have to quiet yourself. Part of quieting is turning off the internet, turning off the radio, turning off appointments with people. It's very natural for us to try to fill a calendar. We’re taught to maximize our time. As we’re taught to be as efficient as possible, there's a trade off.

YANCEY: I was coming to you expressing the feeling that I'm not with people enough. Do you struggle with those things?

RAFAËL: Definitely. I've been working by myself for many, many years. You have relationships, but overall I spend a lot of time by myself. I like to go to lunch with people and I notice if I don't see anyone the whole day I become unhappy. It's very clear. Then if I set up too many meetings I don't get anything done and I don't make new work. So it's a balancing act. The band Kraftwerk had a rule that the phone was only plugged in for half-an-hour a day. That's the only time they were reachable in the studio. They had this sacred studio time. It's the same for any discipline. If you're practicing ballet you're not going to hold your phone while you do it. If you want to do something you have to really do it.

YANCEY: If you were to think across your life to this point, growing up in the family you grew up in, your career as an artist, making websites — what is this moment where you are now?

RAFAËL: I'm very careful attributing any kind of status to those sales, because it’s just a few people that were bidding and they could get bored. I'm very aware that things could be very different in three months. Maybe it's a trend, maybe it will persist, I don't know. I do think this idea of attaching value to digital things is interesting and might persist.

YANCEY: Value creation being divorced from materialism is a great thing. The agreement that code can create value in all kinds of forms, not just code having value as Facebook or whatever, is important.

RAFAËL: That's exactly how I feel when people say, “What's new about this internet?” What’s new is it's not ad-based. The NFT thing is fascinating and I'm happy I jumped in. It seems a little bit too good to be true. I hope it’s just the beginning.

Listen to the full conversation with Rafaël, which explores his creativity and his creative practice in more depth on the web, Spotify, or Apple.

LINKNOTES

Rafaël’s Good Point podcast w/ Jeremy Bailey (recommended!)

Today’s interview is the final episode in the first season of the Ideaspace interview series. You can read or listen to all 18 episodes of the first season here. A second season will begin in the fall. The Ideaspace will publish less frequently during the summer.

Thanks as always for reading and listening.

Peace and love my friends,

Yancey

Headspace and time and attention are key, so the lack of attachment to items mentioned by Rafael here is freeing. An artist or creative can see the place for peace in one's life, and how it works to allow for branching networks of content.