2020 year in review

Reviewing what we explored together this year

Sup y’all and welcome to the final edition of the Ideaspace in 2020. It’s great to be with you.

I’m in no position to summarize what happened this year and I’m not going to try. But this past week I’ve kept thinking back to a slide I made for a talk back in 2017 to illustrate the shift from “old growth” to “new growth” that our growing challenges were calling for.

As we exit 2020, it strikes me that this has actually started to become true. The column on the left represents where we were entering 2020. The column on the right represents where we’re moving as we leave it.

To be clear, in no way does this mean hard times are behind us or our challenges are on the verge of being solved. We can all look around and see this is not a thing to be celebrated and that there are almost certainly harder times ahead. But this year we could feel a shift. The winds changed.

Two separate conversations I had with CEOs way back in the pre-COVID world gave me a sense of how our values were changing.

The first was with the CEO of an outdoors company, which I wrote about in Post-capitalism for Realists:

The other night I was invited to dinner with several wealthy and powerful people. This is not a normal thing for me. During appetizers and drinks I was a wallflower, but opened up over the first course when my dinner companions asked what I did.

“I just wrote a book,” I responded.

“Interesting! What about?” they asked.

“How the world was overtaken by the belief that the right choice in any decision is whichever option makes the most money,” I replied. “My book tells the history of that idea and what we should do instead.”

A mix of expressions greeted me. Some people leaned in with curiosity. Some leaned in with annoyance. Others were already looking for somebody else to talk to.

“The idea that all decisions are about money just isn’t true,” the group responded. “Companies think about profits, sure. But profits are a result of good decisions, not the reason for them.”

At this moment a new person sat down to join us. He turned out to be the CEO of an outdoors company. Not the founder — someone from the private equity firm that had bought a controlling stake. After some pleasantries, I asked the outdoors CEO a question.

“If someone were to show you that the future prospects of your company and the way of life your product enables would greatly benefit over the long-term by investing in the sustainability of your products, and even things like planting trees, right now, could you see the case for that? Can you imagine doing that?”

Heads turned towards him.

“I know what you’re trying to do, ” he said with a smile. He went on to say this wasn’t his company’s job.

This response wasn’t unexpected. I was asking him to consider investing financial resources into creating non-financial returns. Any CEO would say no to this. There wasn’t a financial ROI. Still, I asked the question again.

“I hear that,” I said. “But you’re the CEO of a company that helps people enjoy the outdoors. Your whole product space could disappear as temperatures warm. Couldn’t the most profitable thing you could do in the long run be to make those investments now?”

“I see what you’re trying to do,” he said again, his smile tighter this time. “But the best we can do is to tell people what they can do on their own.” He went on to mention some of the charities his company supported.

Not wanting to be rude, I let the conversation drop. Soon after I made eye contact with the people who had debated the dominance of financial value with me moments earlier. I could see in their eyes that we were thinking the same thing: here was a real-life example of our limited thinking about value.

If I’d pitched the outdoors CEO on a new financial asset to securitize CO2 reduction, a cryptocurrency whose value would be tied to the growth of protected forests, or anything promising a financial return, he might have considered it. But because I wasn’t offering financial upside, my thought experiment was out of the question. We think wealth means we’ve mastered money, but in reality money has mastered us.

Two months later I had coffee with a CEO who is proudly rationalist in their thinking, and yet this conversation went very differently (as recounted in Race to the Top):

I met with the CEO of a particularly impactful company regarding the climate, even though their business has little direct interaction with it. I asked the CEO why they were doing it. What was the ROI?

The CEO thought about how to answer.

“The employees really like that we’re doing it, but that’s not the reason,” they said. “It’s good for our image I guess, but that’s not the reason either.”

The CEO trailed off and was quiet.

“Is it just that it’s the right thing to do?” I prodded.

“Yes,” the CEO replied. “I guess that’s probably it.” But I could tell they weren’t sure.

Investing a company’s financial resources into creating collective value without a direct financial return is very unlike the world we’ve been living in. But the reasons and ways of creating value are changing. The language to justify this new way of thinking feels awkward now because we’re still writing it.

What is the language for decisions like this one? Is this post-capitalism?

By post-capitalism, I mean a world where value isn’t solely defined, distributed, or optimized as financial capital. In post-capitalism, other values — something’s ecological value, its social value, its relational value, and values we’re not aware of yet — will be just as critical depending on the situation.

In a world where capital is less scarce — as our world is becoming, albeit with very unequal distribution — these other forms of value will gradually become as important as financial value. And these are positive-sum values for the most part. One person having that value doesn’t mean another person can’t. It may mean that more people can.

A driving motivation in a capitalist world is for businesses and owners to control the excess financial value created by their operations. In a post-capitalist world these kinds of behaviors would still exist, but there would also be races for new kinds of values and a new willingness to create value without the need to own it.

A key step in this process is finding new ways of quantifying human action and values. From Data Is Fire:

The digital era has changed what we measure and, as a result, changed what’s valuable. A growing amount of human behavior occurs via systems where it’s trivial to track our actions in minute detail. Because of the ease of measurement, our ability to define discrete values has exponentially increased, as have alternative forms of exchange based on alternative forms of value. Examples:

Time. Time is a common currency in the digital age. Video games grant access to special features and character upgrades based on time spent playing the game. Video platforms give the option to pay with your time by watching thirty-second pre-roll ads or with money by buying a subscription. Forms of currency based on time are growing.

Loyalty. Loyalty is traditionally a personal/moral value (how each of us individually values our relationships) or an opt-in value (joining a loyalty program or becoming a financial supporter). Loyalty is also now a passive value that can be used to distribute goods and services. Adele invited people identified by an algorithm as her biggest fans to buy tickets to her shows. Rather than let a traditional auction determine who would see her perform — optimizing for who had the most money to spend — she created a transaction that satisfied a financial minimum (tickets cost money) but maximized for a non-financial value (loyalty and community). Loyalty as a metric and multi-value transactions like Adele’s will both become increasingly common.

Social desirability. The most dystopian possibilities are in social scoring systems that algorithmically determine what privileges, goods, and rights someone should have access to. Using algorithms to allot concert tickets is one thing, but when human rights are based on these scores things get hairy. Such a system currently exists in China, and is what conservatives allege happens now when social media networks de-platform them. This direction will be deeply contested for years to come.

A very 2020 example of this was the increasing rise of social commerce: personal subscriptions, OnlyFans, Twitch streams, paid newsletters, and much more. This was all evidence of a new value system around money, what we value, and how we define self-interest.

One way to think about how values change is as a tech stack:

Most technology applications run on what’s called a “tech stack.” This phrase describes how technologies build on each other’s functionality. Here’s a sketch of a website’s tech stack, for example:

Being “lower” in the stack means being core to how the system runs but farther from the end user. The visible is built on what’s less visible.

Imagine this same structure applied to values. The Values Stack has three layers, each built on the one before:

The Moral layer: Our personal and cultural beliefs of right and wrong

The Rules Layer: Expressions of beliefs through laws, rules, and norms

The Incentives Layer: What orients collective action around shared values and goals

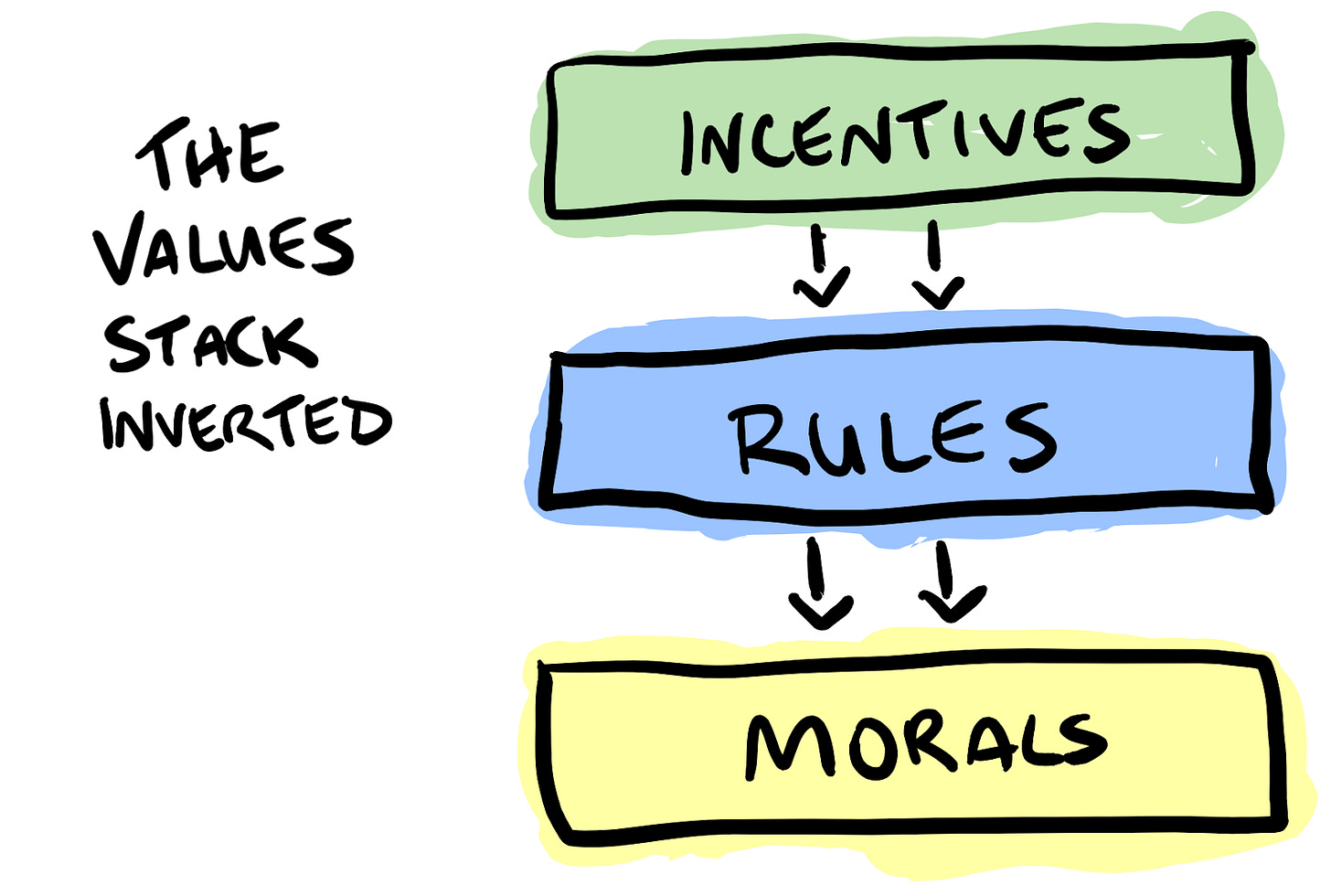

Here it is visualized:

Each layer of the stack is the foundation for the next. A society’s cultural and moral beliefs shape their rules and norms. Those rules and norms shape the metrics and incentives that guide how the society defines success. This is how a value system replicates itself.

The challenge at the start of the 21st century is that the values stack has flipped.

Because of a shift in power, the Values Stack has functioned in reverse. Instead of morals driving rules and incentives, it’s been like this:

Money (an incentive) bought political influence that allowed it to rewrite the rules in its favor. Its power has overruled the moral layer, too.

A talk on “What’s after capitalism?” dove deeper into which values may be shifting.

The Bento Society, a project whose goal is to redefine what the world sees as valuable and in its self-interest, is a direct response to this. Bentoism is a framework that extends our self-interest to our future selves and a collective sense of self:

Shifting how we see self-interest is a scalable solution. It fundamentally changes our relationships to one another without infringing on personal beliefs. It imposes no values beyond an increased awareness of ourselves and each other. Yet it dramatically changes the context and substance of our decisions.

This belief underlies the Bento Society’s theory of change:

Teach individuals the Bento and create an organic community of people who use the framework in their daily lives

Bring Bentoism into organizations, communities, families and other social structures to help set priorities and shift our horizons

Fund and conduct research, projects, and forms of media that better define this new map to what’s valuable and in our self-interest

Where might this ultimately lead? As This Could Be Our Future explores, we can extend these ideas into a near-sci-fi future thirty years from now.

By 2050 the Bento Society’s mission has become a reality. By then:

A Bentoist view of self-interest becomes as accepted and invisible a default as short-term individualism is today. Making decisions to benefit future parties and a wider array of stakeholders will be seen as rational and important to success in all facets of life.

The values used in collective decision making will expand from primarily financial concerns to a wider spectrum of value that includes social values, ecological values, local values, future values, and so on.

New tools like value-added credits (VACs), a government-backed currency that rewards long-standing value-creating businesses and community hubs, introduce new forms of value into traditional currencies.

Advertising and newsfeed algorithms are repurposed to create peer and mentorship circles that increase social value

“Affirmative algorithms” use the logic of reverse Dutch auctions to match price and competency minimums with need maximums for the distribution of public goods

The Bento is a universal UI that puts people in control of their relationship with external technology (i.e. show messages from my Now Us, alert me to things relevant to my Future Me goals, keep me on my Now Me tasks, block everything else)

The Bento Society publishes the book Value in the 21st Century in 2035, which proposes standards of measurement for more than a dozen critical non-financial values, from loyalty to fairness to gross domestic value (GDV), that are critical to thriving in the 21st century

This is still the vision and this project is underway. In 2020 the Bento Society hosted more than 100 events around these ideas for people around the world. In the new year the Bento Society will announce new projects and initiatives to further that mission. You can follow along here.

Finally, if you haven’t yet set aside time to think about what you want out of the coming year, I highly recommend watching The Yearly Bento to help you take stock of the year that was and set your goals for 2021. Watch it here.

Thanks for sharing brainwaves this year. Peace and love my friends,

Yancey